LETTERS FROM THE GLOBAL PROVINCE

Vienna Part I: Liberating the Unconscious, Global Province Letter, 18 June 2014

Freud Murmurs. As May was winding down, we had the very able concierge Wolfgang at the Hotel Sacher root out a psychiatrist who could tell us how Vienna of today regards Sigmund Freud. As it happens, Professor Alfred Pritz, the rector of Sigmund Freud University, on very short notice, made room for us late on a Friday afternoon. So we taxied to the other side of Vienna in order to learn whether Freud still had his hand in the mental stew of the city.

World War II dealt a mortal blow to analysis Freud style in much of the world, but after a few decades the Master did come out of hiding and once again is making himself felt in many corners of the globe. SFU thrives by teaching not only about Freud but about other therapeutic geniuses, maybe some 70 in total. The school has global reach and attracts students from many countries.

One symbol of Freud’s resurrection in Austria is the new building Pritz is erecting, to the tune of $25 million, to better house the university. Amusingly, Pritz had a minor tussle with the city about naming the street where it will be located. At first it was to be Sigmund Freud, but that was taken to be disparaging of Anna Freud, so now it will be on Freud Square. The city then wanted to give the university address No. 2, but it has since relented and put the school down for No. 1 Freud.

Freud in Close Knit Vienna. Freud still attracts our interest, because it was his artful introduction of the unconscious into an early-20th-century, tightly knit milieu of Viennese cultural leaders, scientists, and adventuresome thinkers that allowed Austria, then in decline, to put its stamp on the intellectual life of the modern Western world. Eric Kandel’s Age of Insightbrilliantly portrays Vienna’s impact on how we think about ourselves and the world around us, making clear that Expressionistic Vienna revolutionized the relationship between the somewhat unknowable aspects of our being and the elusive universe in which we try to function.

Evidence abounds that Austria of yesteryear—and of today—keeps the unconscious in chains and that we are still hard pressed to emancipate it. Empress Sisi (Elisabeth), the Empire’s longest serving empress, was a desperately unhappy woman who came from a much less regimented Bavaria into the straitjacket life of the Austrians:

After enjoying an informal and unstructured childhood, Elisabeth, who was shy and introverted by nature, and more so among the stifling formality of Habsburg court life, had difficulty adapting to the Hofburg and its rigid protocols and strict etiquette. Within a few weeks, Elisabeth started to display health problems: she had fits of coughing and became anxious and frightened whenever she had to descend a narrow steep staircase.

Imperial Austria was bound up with strictures and rules that did not allow for a free play of the spirit. Even those at the top of our society are hard put to escape the mental repression that wafts through the corridors of modernity. So today in Austria, one detects an inbred passion for process and rules, whatever the cost.

The Spanish Riding School. Every visitor should view horses at work in the Spanish Riding Academy. The horses learn to dance and do lovely moments. Yet they are also automatons, and we get no hint of what goes on inside their nervous systems as they perform for us. At moments the equestrian ballet looks to be the shuffle of marionettes, not of flesh and blood.

We watched the morning rehearsals, spellbound for more than an hour. At one point we were asked by a ticket lady what we were doing in the reserved seats we occupied. She did not remember that she herself had directed us to the seats. It seems she had become one with the mindless clockwork that makes for somewhat soul-less perfection at Michaelerplatz and Josefsplatz.

Black Camel. Eventually one finds one's way to the Black Camel, the restaurant and the crossroads, where all Vienna, all Vienna that counts, congregates. There you will find politicians, artists, trendies, opera buffs, journalists, and somebody you met last week but did not quite catch his name. In a small big town, this is probably the epicenter.

Black Camel. Eventually one finds one's way to the Black Camel, the restaurant and the crossroads, where all Vienna, all Vienna that counts, congregates. There you will find politicians, artists, trendies, opera buffs, journalists, and somebody you met last week but did not quite catch his name. In a small big town, this is probably the epicenter.

Most likely you would start with the steak tartare and of course we had a double portion. At the table opposite were an odd couple, a little worse for wear, who came an hour before we arrived and were there when we left. Their Scottie was tucked under the table, nestled atop their feet. They peruse a ready supply of books and magazines when they are not chatting with the help. The restaurant clearly is their home several nights a week.

Zum Schwarsen Kameel takes its name from the original owner but also has cryptic meaning in the Islamic world with which Vienna long has had a connection:

In the year 1618 Johan Baptist Cameel acquired a building on Bognerstrasse in old Vienna, around the corner from St Stephens Cathedral to open his market shop to purvey the aromatic spices and exotic foods which were beginning to arrive from the “Orient” with Vienna as one of the key centers of trade routes to the Ottoman Empire. With a play on his own name, he called it “Zum Schwarzen Kameel” (The Black Camel)

Of an evening, order and a bourgeois sensibility obtain. But then, perhaps halfway through one’s meal a raffish figure in a bowler hat and slightly tattered formal wear meanders into the room and plunks his worn Victrola on a serving table. He winds it up and out pours strains of music perhaps from the 1930s, coated with a scratchiness that proves to diners that we have antique sounds in our midst.

It perfectly sums up Vienna. Beneath the ever-present mellow pastiche of sachertortes and whip cream lies a colorful but often tortured history as well as a psychodrama that is not to be denied. And that is why Mr. Freud still has plenty of work to do in these precincts. Despite the obdurate cheerfulness that greets any visitor to Vienna and the sturdy efforts to repress mental agonies past and present, the unconscious refuses to exit the stage. It wants out.

P.S. We found that the best present offered in the gift shop of the Freud Museum is a simple pencil eraser. It bears the word REPRESSION on it.

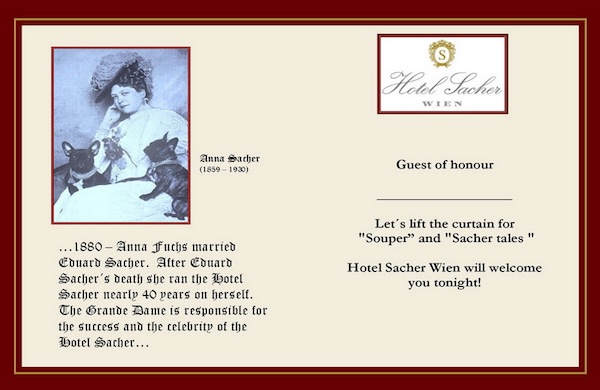

P.P.S. Reasons abound to stay at the Hotel Sacher when in Vienna. For starters it is just across the street from the Opera.

P.P.P.S. Freud met a great deal of resistance from the Vienna medical establishment when he tried to peddle his notions about hysteria and the human psyche on his return from Paris. That he put such a stamp on the city’s and the world’s thinking is all the more remarkable when we understand the rigidity he had to overcome. For more on this, look into his eminently readable An Autobiographical Study.

Home - About This Site - Contact Us

Copyright 2014 GlobalProvince.com