LETTERS FROM THE GLOBAL PROVINCE

Somebody You’d Drink Wine with on the Fourth of July, Global Province Letter, 10 July 2013

Expansive Thoughts. The factotums who rule airports make sure you do not hug the curbs in front of terminals for more than 5 minutes these days. As outlaws, we have to find a grassy spot 10 minutes away, awaiting there a call from the passenger we are about to meet. This leads to very global thinking. Planes from all about the world swoop past us on their way to or from the nearby runways. Our book in hand, Robert Camuto’s Corkscrewed, transports us to French wine country where a few special small growers create vintages of unusual character. On the radio, Aaron Copland’s Rodeo takes us well into a West of yesteryear. This day finds us musing by a landing strip instead of soaking up local festivities.

It is the Fourth of July. But we could not be further from the parades or fireworks. They are as remote for us as the shots fired at Concord that were heard round the world. We had a quiet Fourth this year, as did many. It was meditative. Amidst the confusion of this new century, we wondered whom we would most like to be with and what they would be about.

From the West Coast, for example, came a greeting from an acquaintance of 30 years. He said, “You do good work and have been a good friend.” Yes, that is what we would like to be and that is what we would hope to find in our friends. We are reminded on this day that mostly the world has granted us quality friends who do quality things, with a comic scoundrel here or a wayward lass there proving to be the rare exceptions.

Corkscrewed. On a holiday, especially on a summer moment when we should be especially relaxed, it is vastly more fun to read Robert Camuto than America’s commanding wine critic Robert Parker, or England’s ever spritely Jancis Robinson. Camuto tells us enough about wine, but what his books are really about are the thoughts and antics of the most interesting winemakers. In each of his books, one particularly stands out above all the rest:

Corkscrewed. On a holiday, especially on a summer moment when we should be especially relaxed, it is vastly more fun to read Robert Camuto than America’s commanding wine critic Robert Parker, or England’s ever spritely Jancis Robinson. Camuto tells us enough about wine, but what his books are really about are the thoughts and antics of the most interesting winemakers. In each of his books, one particularly stands out above all the rest:

What distinguished des Ligneris’s winemaking was his meticulous attention to detail. When it was time to replant vines, he waited seven years after ripping up the old vines in order to let the soils rejuvenate.

Yet des Ligneris was publicly ridiculing as a charade the seventy-year-old French wine appellation system—the very same system that maintained the status of his family system. He helped found a group of winemakers…who called themselves paysans-vignerons; they were asking for the transformation of French winemaking along environmental, ethical, and certain esoteric lines, with the stated goal of defying standardization.

In the wine world, it seems, the noteworthy producers are small production, contrarian fellows who are obsessed with quality and who take humorous, rebellious joy in turning up their noses at the wine establishment.

Curiously they are not the new boys in town. Generally they have inherited a wine estate that has been in the family for generations. They are rebels who come from local terroir. One might feel much the same about Ciro Biondi, an Etna wine producer whose family has been there for decades and who provides welcome relief in Camuto’s Palmento (his book on Sicilian wine) when set against the many well-heeled arrivistes who have plunked wine estates in the same region. In wine and in many, many other product areas, the rebel is not firing guns but is training his sights on quality, that which was lost in the mass-market era.

Late in 1968, after the riots in Paris, we ourselves toured the Bordeaux region with a very distant uncle who certainly knew all the great wines and who had reserves of his own that surpassed even the tastings from the chateaux. Often, on our visits, we had a sample of wine right out of the barrel. Though some wine lovers scorn present-day Bordeaux vintages, we feel that the vintners we met then had the same thing going for them as des Ligneris—wine had been in their blood and their families for generations. Then family tradition ensured that the wines of a particular chateau were of the first rank. No longer. Now any newly rich Tom, Dick, or Harry can own a top ranked chateau, and the wine fully encompasses all the foibles of the new owners. Today we dearly need rebels who shout out for quality.

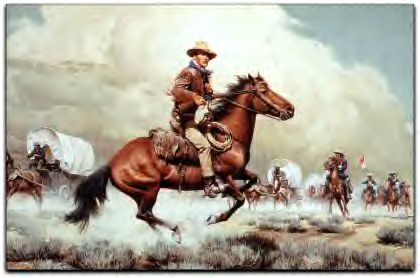

Rodeo. The best Rodeo is not Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills but the Rodeo of Aaron Copeland, the work of a Brooklyn boy who could made us think he knew all about prairie America. Somehow one can envision wide open spaces and rough, buckskin-wearing men who are not daunted by huge herds or rustlers or savage storms.

His prairies were peopled by a different kind of individualist than the rooted French and Sicilian winemakers whose families had cultivated a patch of ground for generations. It was a different sort of fellow who prowled along the frontier, which was ever moving West. These cowhands made America what it is, according to the great American historian Frederick Jackson Turner. Here is Wikipedia’s summation of Turner:

Turner's "Frontier Thesis", was put forth in a scholarly paper in 1893, "The Significance of the Frontier in American History", read before the American Historical Association in Chicago during the World's Columbian Expostion (Chicago World's Fair). He believed the spirit and success of the United States was directly tied to the country's westward expansion. Turner expounded an evolutionary model; he had been influenced by work with geologists at Wisconsin. The West, not the East, was where distinctively American characteristics emerged. The forging of the unique and rugged American identity occurred at the juncture between the civilization of settlement and the savagery of wilderness. This produced a new type of citizen - one with the power to tame the wild and one upon whom the wild had conferred strength and individuality.[11] As each generation of pioneers moved 50 to 100 miles west, they abandoned useless European practices, institutions and ideas, and instead found new solutions to new problems created by their new environment. Over multiple generations, the frontier produced characteristics of informality, violence, crudeness, democracy and initiative that the world recognized as "American".

Soaring on the Fourth. With jetplanes and Camuto and Aaron Copeland, we meandered, our minds going afar. We thought of the knights of wine, chaps with different challenges than those that faced the rough and ready folks who dueled with Jackson’s frontier. Now the gunfighters are men of eccentric but firm character whom I would like to drink with on the Fourth. Men of quality who will have no truck with mediocrity.

P.S. We say that Copeland’s music reminds us of the prairie, but we discover in Classical Net Review that he was late to the term himself. “"Prairie Journal" has a curious history. Copland originally titled the work "Radio Serenade." CBS, who commissioned it, decided to use the piece as part of a promotion. It invited listeners to send in their suggestions for a new title, to be picked by the composer. In the meantime, it called the work "Music for Radio" (the title under which you normally find it) until the contest winner was announced. Copland found no title completely satisfactory but chose Saga of the Prairie as a subtitle. Now the piece was known as "Music for Radio: Saga of the Prairie." In 1968, when radio no longer commanded the attention it had in the 30s, Copland renamed the piece "Prairie Journal."” Many of the composers who steadfastly wrote ‘American’ music in the early 20th century were émigrés from Europe, not at all familiar or comfortable with agrarian America.

Home - About This Site - Contact Us

Copyright 2013 GlobalProvince.com