LETTERS FROM THE GLOBAL PROVINCE

Flirting with the Unknown, Global Province Letter, 9 February 2011

I sat upon the shore

Fishing, with the arid plain behind me

Shall I at least set my lands in order?

London bridge is falling down falling down falling down

Poi s'ascose nel foco che gli affina

Quando fiam uti chelidon--O swallow swallow

Le prince d'Aquitaine a la tour abolie

These fragments I have shored against my ruins

Why then Ile fit you. Hieronymo's mad againe.

Da. Dayadhvam. Damyata.

[from a Hindu fable: 'Give, have compassion, have self control']

Shantih shantih shantih ---from T. S. Eliot’s Wasteland, 1922

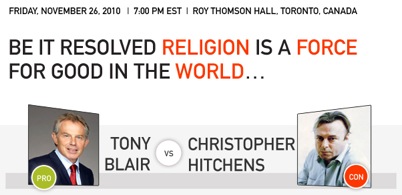

Tony Blair vs. Christopher Hitchens. Last November Tony Blair and Christopher Hitchens debated in Toronto: “Religion is a force for good in the world,” Blair taking the pro stance, and Hitchens battering religion. This was a remarkable event in many regards. First off, both the debaters demonstrated a high degree of civility and mutual respect, not embracing the shouting and meanness that pours out of our cable channels. Secondly, they were debating a question so big and imponderable that we knew in advance that there would be no resolution. It is a sign of health and maturity when people of intellect joust respectfully and tackle huge matters where there are no real answers. Basically Blair, a recent convert to Catholicism, admitted that religion had warts, but that it did so much good throughout the world. Hitchens, adamant atheist, afflicted with throat cancer, forcefully put the case that religion sapped the life out of men and societies. The lengthy debate was much noticed about the world.

Declining Fortunes of Institutional Religion. Of course, this is a very old debate, only slightly re-invigorated by the sprightly performances of Blair and Hitchens. In some regards, the subject matter made both look like dated artifacts from the last century. At least in the more developed countries the number of parishioners in most religions are in decline, not only because people of full stomach and a measure of prosperity don’t feel the call of faith as strongly, but because organized religion does not answer very well to modern life. The plummeting fortunes of all the major denominations in the United States have been widely reported. And church leaders are wringing their hands and furrowing their brows over this meltdown. It would seem that the bright spot for monotheists, amidst the decay, is found amongst the megachurches that are non-denominational, unlinked to any of the great faiths, and which appear to be doing a land office business. The decay of most churches is equivalent to the fast erosion of America’s giant corporations: they have been forced to retrench rapidly in the face of declining finances and a loss of adherents. Religion, too, has been shaken by the tumultuous upheaval that has come to all parts of America in the 21st century. Organized religion, at the moment, does not so much have to deal with its goodness or badness: it has to find relevancy to peoples who have been turned inside out and turned away from it.

Freud’s Last Session. We read in the Wall Street Journal.of an adventurous production of Freud’s Last Session in West Palm Beach, Florida, featuring an imaginary debate between C.S. Lewis and Sigmund Freud. “What ensues is a cross between an urbane conversation piece and a knock-down-drag-out debate over the existence of God.”

What the reviewer likes “most about Mr. St. Germain's pungently literate script is that neither character gets the upper hand. To be sure, both men carry a full load of intellectual gunnery, and each is given his fair share of snappy comebacks (though never so snappy as to make the dialogue sound coy or stagey).” Correctly, in this play, no point of view wins, because once again an unanswerable question is elucidated by the brainy contestants.

We, of course, have not seen the play, but we suspect it deserves a very important, very compelling footnote. Freud may not have believed in God or gods, but it is fairly clear that he came to understand that a worshipful, religious instinct is built into human character. In his view, its role was to mediate between the individual and the claims of both nature and society. That said, he acknowledged, in the end, that is was an integral part of the human spirit. He wrote copiously about religion, attempting to understand the phenomenon. At times he may have been scornful of it, but understood that it was here to stay, not something that could be washed away by psychotherapy or evolutionary process. The pressing question is not to claw over the existence of God, but to reckon with man’s innate spirituality.

In other words, modern institutional religion has gone far afield from modern man. But religion and the religious instinct is not going to go away. Yet the problem is that people unmoored may take up false idols, something warned against in the Commandments and in most of the world’s major religions. As says Exodus, “God spake all these words, saying, I am the Lord out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. Thou shalt have no other gods before me.”

Left to their own devices, men of our age worship Mammon and unseemly wealth, confuse splinter politics with religion, make wrenching over-the-top, unnatural commitments to sports and jobs and sundry other fetishes, pursue a 1,000 obsessions with unseemly passion. We are in fractious times where all manner of men treat their ideas as holy writ, such that they cannot achieve the compromises that make communities work. If the religious instinct is not turned to constructive use, it becomes a frenzy that grabs hold of men, immolating them and those around them. The religious instinct can attach itself to the basest of causes. In this regard, we should never forget Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements.

What Religion Might Do? Turns out, there’s plenty for religion to do. It could wrestle with epidemic human depression for which the therapeutic community really has no answers: depression is spreading faster than viruses throughout the developed world. It could tackle growing ignorance: America is currently growing dumber: historically the churches brought along the urban poor, Bible reading being a goad to literacy. It could promote community and cohesiveness at a time when marriage, and village, and politics, and churches suffer from the canker of divisiveness. It could do battle with all the digital technologies which largely put walls between people, substituting virtual for real communication. There are huge questions with which religion can struggle, since neither science nor government nor academia have anything to offer.

Reclaiming the Wasteland. T.S. Eliot in his Wasteland could have been pointing to the ecological tribulations of today’s earth. But, instead, he was dealing with the spiritual desolation of global man. Of a man cast up on the shore alone.

Ultimately the chore of religion today is to revive our philosophical instinct, so that we duel with great unknowable questions, and get outside our cubicles and our green, and yellow, and red boxes that we like to call houses. The common aspect of our discussion these days is minutia. We are exalting nanotechnology. Our business whizzes spellbind their executive masters with micro-marketing. Our political savants pander in the worst ways to small slices of America—their base—and not to the whole of our citizenry. There is a smallness of mind, which we must overcome. Otherwise, we are condemned to be prisoners of the trivial.

In Berkeley in the 1960s, when the Free Speech movement rattled the University of California, students and hanger-ons thought they were at the center of the universe doing things that would remake the earth. They weren’t. And it wasn’t. Berkeley is just a small adjunct to San Francisco—California’s second city—whose economic vitality is draining away. The challenge is lead the good and purposeful life, while realizing we live at the margins of the universe.

In the end, religion perhaps can help us overcome narcissism, which makes modern life the spiritual wasteland sketched by Eliot in 1922. Religion and metaphysics can help us understand that we’re just a brief small bubble in the history of the universe. Where we are and who we are only achieve significance as we learn to think about anything but ourselves—to dwell on other people, other lands, other universes. Narcissism is the central spiritual enemy of modern man, setting the stage for any religion that wants to fight the good fight. Freud celebrated this affliction but did not beat back the unnatural hold of Narcissus on modern man.

In the end, religion perhaps can help us overcome narcissism, which makes modern life the spiritual wasteland sketched by Eliot in 1922. Religion and metaphysics can help us understand that we’re just a brief small bubble in the history of the universe. Where we are and who we are only achieve significance as we learn to think about anything but ourselves—to dwell on other people, other lands, other universes. Narcissism is the central spiritual enemy of modern man, setting the stage for any religion that wants to fight the good fight. Freud celebrated this affliction but did not beat back the unnatural hold of Narcissus on modern man.

P.S. In Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam bewails the decline of community in these United States. He believes re-invented religion will be the antidote for this dilemma. He further thinks that megachurches give us some hints of what the new religion will look like.

P.P.S. Years ago there was a wonderful engaging professor at the University of Connecticut called Bob Warnock. He had a rule of social discourse: that is, never discuss religion, sex, or politics. Inevitably, we can testify, he did all three. As he and we should. Having migrated from mathematics to literature in his career, he understood that for every rule, there’s another that contradicts it. Since he wrote much about James Boswell, he also much understood the need for wandering, enlightened conversation that ranges well beyond one’s ken. We should be able to have fine discourse about bold topics without losing our social equanimity.

P.P.P.S. Peter Munk almost brought himself and Canada greatness by sponsoring the Blair-Hitchens shootout. But then he charged for the video replay, showing himself not quite up to the challenge. You can find the debates, nonetheless, on YouTube. He’s a Canadian goldbug of Hungarian heritage who, we suppose, is trying to show that he’s in the same league as George Soros. But he’s a bit penny ante.

P.P.P.P.S. German philosophers in particular have done much work on the limits of knowing. There are all sorts of things we cannot know. So you might say, “Why should we bother with questions that defy us?” Thinking about the elusive stretches the brain and spirit, and even makes us better at our ordinary tasks. We always enjoy the fact that the great bridge builder John Roebling was mentored by Hegel and studied philosophical questions right up to the end. Philosophy consumed his leisure.

P.P.P.P.P.S. Graphis, the world’s most important graphic arts publisher, came out with a lovely book called Prayers for Peacea few years back. Ironically the book was excluded from evangelical bookstores because it included prayers from religions outside the Christian vale. Despite all the missionary activity and ecumenical platitudes, a host of religions are fighting a rearguard action against globalism and the community of man. We cite one prayer:

Pray not for Arab or Jew,

For Palestinian or Israeli,

But pray rather for yourselves

That you may not divide them in your prayers,

But keep them both together in your hearts.

-----Rabbi Stanley Ringler

P.P.P.P.P.P.S. The claims of the state and the claims of religion have always muddled both institutions. In their struggle against each other, the state forgets its mission of promoting the general (earthly) health and welfare, while the church loses all of its spiritual glow. In the story of The Road to Canossa, we see this with utter clarity. Pope Gregory, reacting to Henry IV’s appointment of church officials, excommunicates the determined king. Finally, Henry has to go to Canossa and beg the Pope’s forgiveness to end his exile from the Church. This all just amounts to an unseemly power struggle that brings luster to neither and does naught for mankind either on earth or in heaven. This was known as the Walk to Canossa or, in the Italian, l'umiliazione di Canossa. Neither the Roman Catholic Church nor the Holy Roman Empire progressed as they should during the Middle Ages, because they had the wrong view of themselves.They were both lesser vestiges of the Roman Empire.

P.P.P.P.P.P.S. The claims of the state and the claims of religion have always muddled both institutions. In their struggle against each other, the state forgets its mission of promoting the general (earthly) health and welfare, while the church loses all of its spiritual glow. In the story of The Road to Canossa, we see this with utter clarity. Pope Gregory, reacting to Henry IV’s appointment of church officials, excommunicates the determined king. Finally, Henry has to go to Canossa and beg the Pope’s forgiveness to end his exile from the Church. This all just amounts to an unseemly power struggle that brings luster to neither and does naught for mankind either on earth or in heaven. This was known as the Walk to Canossa or, in the Italian, l'umiliazione di Canossa. Neither the Roman Catholic Church nor the Holy Roman Empire progressed as they should during the Middle Ages, because they had the wrong view of themselves.They were both lesser vestiges of the Roman Empire.

P.P.P.P.P.P.P.S. We would suspect the meditative techniques wrapped in a religious veil may be the best antidote to civilized man’s growing struggle with mental depression.

P.P.P.P.P.P.P.P.S. We find it fascinating that a Wharton essay is able relate a person’s happiness to his economic well-being amd the leisure he can devote to social relationships and other pastimes. But nowhere does it point to spiritual wellness as a major ingredient in happiness.…..

Home - About This Site - Contact Us

Copyright 2011 GlobalProvince.com