LETTERS FROM THE GLOBAL PROVINCE

The Forest Primeval, Global Province Letter

26 January 2011

THIS is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks,

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.

Loud from its rocky caverns, the deep-voiced neighboring ocean

Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the forest.

This is the forest primeval; but where are the hearts that beneath it

Leaped like the roe, when he hears in the woodland the voice of the huntsman?

Where is the thatch-roofed village, the home of Acadian farmers --

Men whose lives glided on like rivers that water the woodlands,

Darkened by shadows of earth, but reflecting an image of heaven?

Waste are those pleasant farms, and the farmers forever departed!

Scattered like dust and leaves, when the mighty blasts of October

Seize them, and whirl them aloft, and sprinkle them far o'er the ocean.

Naught but tradition remains of the beautiful village of Grand-Pré.

Ye who believe in affection that hopes, and endures, and is patient,

Ye who believe in the beauty and strength of woman's devotion,

List to the mournful tradition still sung by the pines of the forest;

List to a Tale of Love in Acadie, home of the happy.

-----Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Evangeline. If you were lucky, you might just have listened to Evangeline in high school, as a spectacled Mrs. Prescott (or whatever your starry-tongued schoolmistress of English was called) tried to draw you into the magic of Longfellow, another one of those uplifting 19th century poets, who, like Whitman, could communicate the majesty of North America. Longfellow, especially, saw its trees and forests with great particularity. He also pictured for us the village smithy who hammered away below the “spreading chestnut tree.” Thoreau, you will remember, declared his independence and individually by living out in the woods near Walden Pond. Our last century was very much about trees.

The World’s Remaining Forests. Fact is, there just aren’t too many English teachers conjuring up ancient times and thousand-year-old forests these days. In fact, today’s slew of school marms and misters mostly give vent to their neuroses and their complaints about society, instead of luxuriating in wider thoughts and awesome spaces. By now, too, the courses are no longer called “English,” but “comparative” something or other. The lessons are not meant to teach love of literature or the beauty of ordered grammar, but to give voice to politically correct agendas of the left and the right.

The student no longer has to memorize verse, although the late and great Yale Professor Henri Peyre said one does not begin to understand a poem until he can recite it by heart. The English courses that roamed across America’s spaces and comprehended our metaphysical destiny are just a memory, the experience of previous generations.

And so too, the great forests. They are getting to be just memories. We are told that 80% of our forests have disappeared, half of that pitiful shredding having occurred in the last 30 years. Worse than termites, the peoples of all nations are stripping the foliage away at an alarming rate. It’s clear to green devotees that this devastation has everything to do with global warming, erosion, floods, and you have it. We’re wrecking our home.

More immediately, however, we are chewing up our quality of life as we take the trees away. For they have a great deal to do with our peace of mind, quality of food, and even our artistry. While mankind probably understands that deforestation is a global problem, we are less insightful about the carnage it is inflicting on our daily comforts and our Hobbesian lifestyle in January of 2011. The barrenness of our planet has seeped right into our lives. The leaves in our frontyards have left us.

Mind and Body. The Japanese think that forests can affect our health in several ways. Many enthusiasts go for walks in the forest to recapture their equilibrium:

Mind and Body. The Japanese think that forests can affect our health in several ways. Many enthusiasts go for walks in the forest to recapture their equilibrium:

“Scientists in Japan have been learning a lot in recent years about the relaxing effects of forests and trees on mental and physical health. Based on their findings, some local governments are promoting "forest therapy."

“Experience shows that the scents of trees, the sounds of brooks and the feel of sunshine through forest leaves can have a calming effect, and the conventional wisdom is right, said Yoshifumi Miyazaki, director of the Center for Environment Health and Field Sciences at Chiba University.

“Japan's leading scholar on forest medicine has been conducting physiological experiments to examine whether forests can make people feel at ease.

“One study he conducted on 260 people at 24 sites in 2005 and 2006 found that the average concentration of salivary cortisol, a stress hormone, in people who gazed on forest scenery for 20 minutes was 13.4 percent lower than that of people in urban settings, Miyazaki said.”

As well, Japanese scientists have discovered that oysters taste infinitely better when the beds they inhabit are infused by runoffs from forest streams. They have come to think that preserving forests has a great deal to do with preserving our own selves.

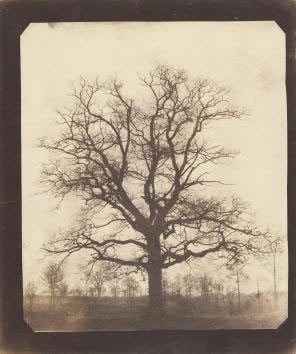

Art. Much of our interesting and most humanistic art stems from wood and trees and forests. The J. Paul Getty Museum currently is staging an exhibition that shows how the tree is an integral part of our esthetic life. “Loosely organized into single tree portraits, trees in the landscape, abstract forms drawn from trees, and daily uses of the tree, the exhibition highlights photographers from different eras, juxtaposing their works to create an interesting dialogue, says Lyden. One of the earliest works in the exhibition is William Henry Fox Talbot's iconic An Oak Tree in Winter (1842-1843), which captures the lace-like pattern of bare branches against a stark winter sky.” At the same time the Smithsonian is showing off a new collection of wood artifacts at “A Revolution in Wood: The Bresler Collection.” This new- found interest of cultural institutions in the tree is a necessary prelude to a popular revival of enthusiasm for things that are green and tall.

Art. Much of our interesting and most humanistic art stems from wood and trees and forests. The J. Paul Getty Museum currently is staging an exhibition that shows how the tree is an integral part of our esthetic life. “Loosely organized into single tree portraits, trees in the landscape, abstract forms drawn from trees, and daily uses of the tree, the exhibition highlights photographers from different eras, juxtaposing their works to create an interesting dialogue, says Lyden. One of the earliest works in the exhibition is William Henry Fox Talbot's iconic An Oak Tree in Winter (1842-1843), which captures the lace-like pattern of bare branches against a stark winter sky.” At the same time the Smithsonian is showing off a new collection of wood artifacts at “A Revolution in Wood: The Bresler Collection.” This new- found interest of cultural institutions in the tree is a necessary prelude to a popular revival of enthusiasm for things that are green and tall.

In other words, now that we are losing forests, we are learning—a prophet here, a scientist there—to put a value on them. We are much like Holly Golightly, Truman Capote’s heroine in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, who exclaims, “Not knowing what's yours until you've thrown it away.” She had fecklessly dropped her cat onto the street, losing what was precious to her, realizing too late its value. In fact, the most astute collectors of American art should focus on American’s connection to nature, for therein lies our distinctive contribution to the visual arts.

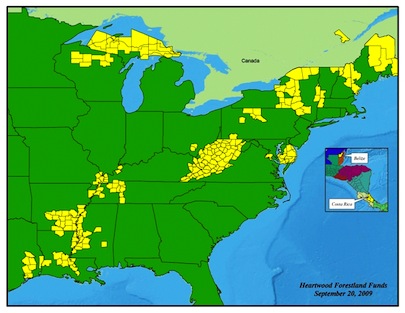

Cash Value at the Margins. The forests and the woods are not only ethereal: they have value in the marketplace. Of course, at the margins, there are financial intermediaries who strive to help us hold on to our trees. A few timber partnerships (perhaps 13 or 20) are available to thoughtful investors who want to own and preserve hard assets that are also helpful to the planet. Forestland Group focuses heavily on hardwoods, overwhelmingly concentrated in the Eastern United States, which are the most glorious and the most valuable of trees. Should you have some noble and thrifty trees of value on your own homestead, you can work with HMI which advises insurance companies about arboreal values and which now can assemble an assessment of valuable woods on your property. Wood is a hard asset worthy of investment particularly because most don’t pay attention to it, so valuations have not gotten out of line.

Cash Value at the Margins. The forests and the woods are not only ethereal: they have value in the marketplace. Of course, at the margins, there are financial intermediaries who strive to help us hold on to our trees. A few timber partnerships (perhaps 13 or 20) are available to thoughtful investors who want to own and preserve hard assets that are also helpful to the planet. Forestland Group focuses heavily on hardwoods, overwhelmingly concentrated in the Eastern United States, which are the most glorious and the most valuable of trees. Should you have some noble and thrifty trees of value on your own homestead, you can work with HMI which advises insurance companies about arboreal values and which now can assemble an assessment of valuable woods on your property. Wood is a hard asset worthy of investment particularly because most don’t pay attention to it, so valuations have not gotten out of line.

Disappearing Pastures. In America we are gobbling up land at a torrid pace, since our developers have been given leave by our governments to dot their homes and buildings about the land, rather than working compactly and leaving green spaces in between. More and more of the population lives in urban sprawls: people are ever more detached from forests and animals and nature.

The Audubon Society knows that much of the U.S. population has never seen a beaver, rarely encounters trees and flowers, and has no time for birds. Realizing this, it has made a considerable effort in recent years to bring nature to cities and towns. Nature groups and timber lovers have the same problem: urban peoples may never experience forests. It’s incumbent on green believers to increase plantings in the cities, lining streets and byways with disease resistant elms and other majestic species. It’s encouraging to see roof gardens that include vegetables, and shrubbery, and even trees. It’s enchanting to see wall gardening, such as that developed by the Parisian Patrick Blanc, that crawls up the sides of buildings. For we will only have forests, if every man has a tree near him that he treasures. Never to be forgotten is Bernard Maybeck, the most charming of West Coast architects, who defended before the city fathers of Berkeley “a noble and thrifty tree” in the middle of one of the town’s streets which the short-sighted wanted to rip down.

As the countryside recedes, we are obliged to bring more country into the city.

P.S. Paint Your Wagon is best remembered for a lovely song called “I Talked to the Trees.” The singer claims he talked to the trees, but they wouldn’t listen to him. That’s fair. For it can be said that we don’t listen to the trees.

P.P.S. One reason Ted Turner got involved with Ted’s Restaurants, which serve buffalo, is that he figured that buffalo herds would expand yet more if they became part and parcel of our menu and our life. That’s as well the challenge for forests and wood and the like—to once again become central to our lives and our conception of ourselves.

P.P.P.S. The Sunday New York Times Book Review (January 23, 2011) was, for a change, very well thought out and asks, in many tantalizing ways, how philosophy affects life and whether a philosopher espousing this view or that view is able to make a success of his own life. It reaches no real conclusion, but the ultimate question posed is a good one. Likewise, for those who worry about global warming and the battering taken by our earth, we must ask them how green are their own valleys. That was the great insight of the American pragmatists: if an idea is worth having, it must have cash value or a payoff, in some sense, for he who espouses it. Do we walk the talk, or just natter on?

Back in the 1960s, the New Criticism pervaded literary analysis. That is, the au courant academics said a poem or a work of art should be looked at without reference to history, or biography, or psychotherapy. The work should be appreciated on its own merits, and our view of it should not be obstructed by side issues such as politics or other trendy thinking. True enough. But at the end of day we can never divorce art, or culture, or philosophy from life, particularly the life of the creator.

P.P.P.P.S. When you have the time, spend an hour or two contemplating the paintings of the Hudson River School, for this was America’s great moment in art. Therein lay nature and romanticism and a hearty American nationalism. You can feel America’s sinews. This was America achieving greatness.

Home - About This Site - Contact Us

Copyright 2011 GlobalProvince.com