LETTERS FROM THE GLOBAL PROVINCE

Home from the Wars, Global Province Letter, August 18, 2010

“We’re a long, long way from home. Home’s a long, long way from us.”—Bruce Springsteen

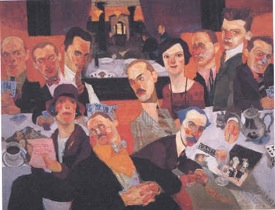

A House is Not a Home. Polly Adler, a woman of ill repute and a madam of powerful connections, trafficked with authors, politicians, gangsters, and anybody else who could scare up enough change. Robert Benchley, New York’s fun-loving mayor Jimmy Walker, and mobster Dutch Schultz all visited her premises and each offered her help and protection. Her establishment provided much more than sex: it was a hideout for Schultz and became a clubhouse for members of the renowned Algonquin Roundtable. She was part of carousing times in New York City, a town that has since lost much of its playfulness which we will bemoan in an upcoming letter about Gotham City. Finally, with a ghostwriter at her elbow, Adler chronicled her madcap life in A House Is Not a Home, the proceeds from which supported her during her last hurrah in Los Angeles.

A House is Not a Home. Polly Adler, a woman of ill repute and a madam of powerful connections, trafficked with authors, politicians, gangsters, and anybody else who could scare up enough change. Robert Benchley, New York’s fun-loving mayor Jimmy Walker, and mobster Dutch Schultz all visited her premises and each offered her help and protection. Her establishment provided much more than sex: it was a hideout for Schultz and became a clubhouse for members of the renowned Algonquin Roundtable. She was part of carousing times in New York City, a town that has since lost much of its playfulness which we will bemoan in an upcoming letter about Gotham City. Finally, with a ghostwriter at her elbow, Adler chronicled her madcap life in A House Is Not a Home, the proceeds from which supported her during her last hurrah in Los Angeles.

Of course, Adler’s retreats were bawdy houses, not homes. We suspect for some customers that they were escapes from the vicissitudes of home life. The unhappy truth of our present era is that, in so many cases, houses about our land, where families bed down and break bread, are not homes either, domestic bliss having gone up the chimney in a puff of smoke. Houses that are not homes have grown aplenty. Through 2008, the U.S. divorce rate was at 40%: it has declined somewhat since. Surely that tells us that the flood of building since WWII has created a plethora of barebones housing, but a modest quantity of real homes and domestic tranquility.

With virtually all institutions in these United States now in terrible disarray, surely it’s time for the home to re-assert itself. We’re nursing a couple of wars, dysfunctional governments, quarreling churches, colleges that can’t teach kids to think or write, and businesses where chief executives are handsomely paid for failure. Indeed, they all have become organizations of ill repute. It’s time to come home. We need the home, our most basic social unit and the fount of true community.

If everything’s broken, we should begin with something small—the home—and get it working again. It could be a retreat from crime, and hurricanes, and financial chaos, and global warming. It should be the place where we generate the creativity to overcome our copious problems. We need homes that take us away from life’s wars.

Ellen Swallow Richards. Curiously the domestic arts have fallen into disfavor. Men and women are all up to more important things, racing as fast as they can through their household chores, stuffing yet more and more into their schedules well away from family life. So home life is done rather badly. The greenspace out front is threadbare, designed for low maintenance and not much else. Reproduction furniture greets one in the hallway. TV and electronic media have displaced conversation. The food comes out of boxes and microwaves. One sense in such houses a psychological vacuum: there’s nothing there. Such dwellings are filled with absence.

Ironically, the real founder of home economics in the United States was a heavyweight chemist who took the household economy very seriously. Ellen Swallow Richards managed to wheedle an education out of MIT and some other schools that were mostly trying to keep women barefoot and pregnant. And she brought the same stubborn determination to the domestic arts:

In 1899, together with Melvil Dewey, director of the New York State Library and author of the "Dewey Decimal System" of book classification, Richards organized the first meeting of diverse individuals interested in what became known as home economics. As chair of these summer conferences in Lake Placid, New York, she helped determine the shape and objectives of this emerging field while developing model curricula. In 1908, at its tenth conference, the group formed the American Home Economics Association and elected Richards its first president, a position she held until 1910 when she insisted on retiring. She also helped found, and finance, the Journal of Home Economics.

Richards did not consider science more important that life in the home. What she wanted to do is put science and practicality into the home.

Domestic Architecture. Perhaps a starting point in revitalizing the home is to build houses that are not sterile boxes. It’s not just factory-type developments for people of moderate means that suffer from cheap materials and a lack of imagination. Even the celebrated houses of famed architects leave much to be desired. Phillip Johnson’s glass house in New Canaan is not a treat inside or out, and suffers from some of the same lack of functionality that blights more than one Johnson structure.

Domestic Architecture. Perhaps a starting point in revitalizing the home is to build houses that are not sterile boxes. It’s not just factory-type developments for people of moderate means that suffer from cheap materials and a lack of imagination. Even the celebrated houses of famed architects leave much to be desired. Phillip Johnson’s glass house in New Canaan is not a treat inside or out, and suffers from some of the same lack of functionality that blights more than one Johnson structure.

We need to look harder at true domestic architects who (a) have an eye for appropriate  decoration and reject sleek bland surfaces and who (b) have made houses, not skyscrapers, their life’s work. We are particularly fond of Bernard Maybeck, a Bay Area architect. His houses were homes. They were dreamlike, full of regal Beaux Arts touches, yet modest in demeanor.

decoration and reject sleek bland surfaces and who (b) have made houses, not skyscrapers, their life’s work. We are particularly fond of Bernard Maybeck, a Bay Area architect. His houses were homes. They were dreamlike, full of regal Beaux Arts touches, yet modest in demeanor.

Maybeck always said he knew he’d built the right house for clients if they managed to landscape it right, completing it with a verdant sympathetic environment. The outside must go with the inside. In fact, owners of Maybeck houses generally do complement them nicely with ample greenery, rejecting the stripped down pinched lawns and depressing, half-pint shrubs that populate our suburbs.

Homes with Character. Houses with interest and bits of detail do not guarantee that the burgher will have a home. So much of homemaking consists of attitude and intangibles. But a bit of homey design is a very good start. In this vein it behooves us to sort through the pages of the New York Times which occasionally features grand, imaginative houses replete with curious detail. Occasionally it will include a folly.

Rokeby, for instance, excites the imagination—a 195-year old estate on the Hudson still inhabited by descendants of the Astors and Livingstons who created this edifice in the first place. Michael DesRosiers, a refugee from Austin, Texas has moved to Lyme, Connecticut and created a whimsical affair, distinguished by its 700 boxwoods, tastefully furnished with very inexpensive castoffs. A French couple, Jean Marc and Solange Mirat, is building a medieval castle in  Arkansas, putting the Old World into the New, and totally ignoring the International Style of Architecture, a creation of the Industrial Age, which has imprinted a sameness on architecture across the world. Houses that delight look like they have been there always, compressing decades or centuries of history inside their frames.

Arkansas, putting the Old World into the New, and totally ignoring the International Style of Architecture, a creation of the Industrial Age, which has imprinted a sameness on architecture across the world. Houses that delight look like they have been there always, compressing decades or centuries of history inside their frames.

These all should be inspirations for our age. For they mock cookie-cutter dwellings, which are so antithetical to the spirit of the home and calcifying of the soul.

Vesta. There’s an American lady in Portugal, now divorced, who’s just bought a condominium in Lisbon (the prices are reasonable there) and is busy imbuing it with her character. Best of all, she has put a statue of Vesta, the Roman goddess of hearth and home, in the front hallway to remind her and her children that a house is meant to be a home.

Vesta is just the Roman name for Hestia, the Greek goddess of the home. The Romans, it seems, were less imaginative than the Greeks, so they stole the Greek pantheon of gods and simply renamed them. “Hestia, Greek Goddess of the sacred fire, was once known as "Chief of the Goddesses" and "Hestia, First and Last". She was the most influential and widely revered of the Greek goddesses.” Despite her initial primacy, Hestia’s importance—to Greeks and Romans and the civilizations that followed—declined through the ages. “Hestia evolved into a lesser goddess in the same ranks of Pan and Dionysus, who was incorporated into the Olympian order in Hestia's place.” Over the centuries she—as well as the home—have lost their place in the sun. Now is the time for their restoration to the center of our cosmos so that we may anchor ourselves as the world tosses and turns.

Vesta is just the Roman name for Hestia, the Greek goddess of the home. The Romans, it seems, were less imaginative than the Greeks, so they stole the Greek pantheon of gods and simply renamed them. “Hestia, Greek Goddess of the sacred fire, was once known as "Chief of the Goddesses" and "Hestia, First and Last". She was the most influential and widely revered of the Greek goddesses.” Despite her initial primacy, Hestia’s importance—to Greeks and Romans and the civilizations that followed—declined through the ages. “Hestia evolved into a lesser goddess in the same ranks of Pan and Dionysus, who was incorporated into the Olympian order in Hestia's place.” Over the centuries she—as well as the home—have lost their place in the sun. Now is the time for their restoration to the center of our cosmos so that we may anchor ourselves as the world tosses and turns.

Boutique Homes. We have said elsewhere that global competition dictates that we forge here, in high cost America, a boutique economy where we strive to produce small run, highly unique products and services that cannot be knocked off by low wage economies elsewhere. Mass manufacturing and mass marketing are outmoded concepts for us, even though our largescale enterprises have not recognized this truth.

As well our houses need to be boutiques that serve as aesthetic and spiritual refutation to the world of mass manufacturing and the daily grind of relentless activity. Each house needs to be one of a kind in order to be a home. And each home needs to be a restful sanctuary inhabited by the goddess of the hearth.

Thomas Wolfe claimed, “You Cannot Go Home Again.” We must prove that to be balderdash.

P.S. If you run out of crises to stoke your blood pressure, you should give a peek to the Hindenberg Omen. All the warning signs are currently up, and it signals a big crash in our stock market. It is the invention of Jim Miekka, a blind mathematician and, we guess, a soothsayer. Of course, any prophet of doom can look pretty good these days, since we are in for a series of small crashes and rampant volatility.

P.P.S. Everybody’s pretty clear that this depression will not be over until unemployment, hovering around 9%, falls and the housing bust gets fixed. Maybe that calls for new kinds of jobs and new kinds of houses. Current housing, of poor design and weak materials, is in decay before it is finished. Obsolescence, a staple of the mass market economy, is dead wrong for us as we go forward. The high tech world prospers by endlessly remaking gadgets and software that don’t need to be remade. That’s not a winning idea when we are trying to plot a sustainable economy. Jim Collins wrote a book called Built to Last—about visionaries who constructed lasting companies. The irony, of course, is that all the companies he mentions churns out things not meant to last. We will have to re-teach ourselves how to make things that last.

P.P.P.S. A gentlemen of our acquaintance just got through installing a new boiler in his basement. One probably does not have a home until one has made and remade one’s house several times. The American Indians, we are told, believed that things that are crafted are inhabited by the spirits of those who make them. Mere interior decoration will not do the trick: one must stain one’s woodwork with perspiration. We’re hoping this selfsame gentlemen will soon share all his reflections, pictures, and calculations about boilers with us on the Global Province.

P.P.P.P.S. A goodly number of New York’s social clubs have really turned into nothing more than average hotels. Money is part of it. But, as well, the membership does not understand fellowship or the value of a plain, good steak. On inspection, you will find that the shoeshine boy has been fired, the drinks are half the size, sloppy dress is common in the public rooms, and the athletic facilities have been sub-divided into small spaces. It’s enough to make any member with a memory a bit churlish.

P.P.P.P.P.S. There’s a delightful website called The Domestic Arts It’s a reminder of all the small things that go into homemaking.

Home - About This Site - Contact Us

Copyright 2010 GlobalProvince.com