LETTERS FROM THE GLOBAL PROVINCE

Global Province Letter: The Play’s the Thing

February 10, 2010

More relative than this—the play's the thing

Wherein I'll catch the conscience of the King- William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Act II, Scene II

The Play’s the Thing. Of course, the irony here is that Hamlet has anything but play on his mind. The play within a play is nothing more than a ruse by him to out the king and seek vengeance against Claudius for the death of his father. And that’s the trouble with play these days: our human tribe is so caught up in obsessive competition, vitriolic polemics, hyper- activity, and collective depression that it has forgotten how to play. There’s a lust to outdo the other fellow, with a sluggish mood hovering about that poisons the air with cancerous alienation. That is why Hamlet is a tragedy, and that also is the tragedy of our age. Play has been turned on end and turned into work.

The Play’s the Thing. Of course, the irony here is that Hamlet has anything but play on his mind. The play within a play is nothing more than a ruse by him to out the king and seek vengeance against Claudius for the death of his father. And that’s the trouble with play these days: our human tribe is so caught up in obsessive competition, vitriolic polemics, hyper- activity, and collective depression that it has forgotten how to play. There’s a lust to outdo the other fellow, with a sluggish mood hovering about that poisons the air with cancerous alienation. That is why Hamlet is a tragedy, and that also is the tragedy of our age. Play has been turned on end and turned into work.

All the World’s a Stage. We prefer instead Shakespeare’s As You Like It wherein “All the world's a stage, /And all the men and women merely players;/They have their exits and their entrances;/And one man in his time plays many parts.” While this is part of a monologue uttered by the melancholy Jacques, it celebrates the human comedy. We’re all merely playing our parts and inevitably getting on with things. In this view, life is a bit fore-ordained, and we are wise to carry out our roles with humor, panache, and, indeed, even with a sense of play. Above all, our mortal coil is not a tragedy, but something that links us to others.

Hurt Yourself. There are chaps who are trying to sail against the bitter prevailing wind that’s blowin’ across the globe. We’ve just finished Hurt Yourself, a collection of plain fun capers that Harry Hurt III originally wrote for the New York Times in a column entitled “Executive Pursuits.”He, in fact, is frantically at play throughout. In it we learn how Harry picked up a $600 custom suit in the back alleys of Chinatown, about his ten minutes of fame as a ballet less-than-superstar, and of his intrepid moments as pilot of a T-51 Mustang. We discovered that the Times canned Hurt in one of its mistaken economy moves. It takes an oddsome fellow like Hurt to play polo on the spur of the moment or to try 10 minutes of quarterbacking at a Jets football practice in memory of his now deceased friend and hero George Plimpton. In an age where fun and play are dwindling, squeezed out by technology, material pursuits, high anxiety, and suicidal busyness, it takes a Hurt to tickle our funnybone. Lately Hurt has put up a website called World of Hurt wherein he tries to train his antic eye on the whole of America.

Why are we not surprised that the Times put him and his column out to pasture? Probably because the Times has always been inordinately ponderous, a knee-jerk enemy of good times and light spirits. Harry the Hurt and that newspaper really never did make music together. He was a discordant note. This is the paper, after all, that instructed a writer who was doing a column on children’s cooking classes to interview a psychologist on the implications for young kids of taking up cooking. Fortunately a chap at Yale, who laughed at this utter editorial nonsense, cooperated and gave a properly trivial, authority-laced quote to put some unnecessary ballast in the article.

You can be sure the Times did not back a stunt of the journalist Richard Harding Davis. One night a hundred years ago in New York City he went from bar to bar gathering people up and then arrived with his carousing crowd to fill the seats and to cheer on the performance of a friend’s play in Manhattan. (Although, we must add, he did put it some time at the Times.) Nor did the Times ever have a playful city editor like Abe Mellinkoff whose San Francisco Chronicle, in the early sixties, sported a front page headline claiming “San Francisco Coffee is Swill.” The grey Times is part and parcel of a guilt-ridden but self righteous city whose Mayor Bloomberg has legislated secular virtue, banning smoking in bars and furiously trying to drive salt out of his fellow citizens’ diets. Hurt was a marvelous organ transplant for the Times, but its flawed DNA rejected him with alacrity.

There was a paper once upon a time, the New York Herald Tribune, that did report on the joys and ebullience of New York City. Back in its day, New York City hearts were still ‘young and gay,” to quote Cornelia Otis Skinner. William Zinsser beautifully tells of its heft and worth in “The Daily Miracle” In its best days, it was owned by the Reid family, sensible Republicans with a sense of humor, back when the Republican Party had leaders of sense and sensibility. The only vestige of the the Tribune that survives is the International Herald Tribune, which was quite a breezy, fun publication for the longest time until the Times bought the whole thing and ruined it.

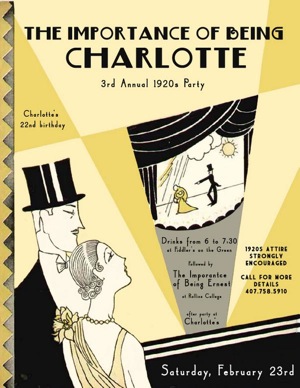

Rollicking Rollins No More. In days of yore, when the Tribune was still alive and well, we’d hear that the college to go to if you wanted to have a good time was Rollins—in Winter Park, Florida. The gossip was that you could really learn a lot about basket weaving there and that the parties were fabulous. We just sent an enquiry to a Florida swamp dog we know who keeps his ear to the ground and he reports that the place has tried to turn serious: no more bon temps rouler. What’s more we are told goodtime schools are a thing of the past. Colleges all are now filled with neuroses, political correctness, a surfeit of community-minded activities, and, above all, a pathology which compels undergraduates to sniff out the trail to their first ill-suited jobs. Fun schools have all become trade schools.

Rollicking Rollins No More. In days of yore, when the Tribune was still alive and well, we’d hear that the college to go to if you wanted to have a good time was Rollins—in Winter Park, Florida. The gossip was that you could really learn a lot about basket weaving there and that the parties were fabulous. We just sent an enquiry to a Florida swamp dog we know who keeps his ear to the ground and he reports that the place has tried to turn serious: no more bon temps rouler. What’s more we are told goodtime schools are a thing of the past. Colleges all are now filled with neuroses, political correctness, a surfeit of community-minded activities, and, above all, a pathology which compels undergraduates to sniff out the trail to their first ill-suited jobs. Fun schools have all become trade schools.

Even ultra-serious people, however, know that our academies have tranformed themselves into purgatories where frantic over-scheduling, humongous amounts of make work, and anxiety-provoking preachiness have supplanted play, commonsense, and education itself. We have previously told how teachers, goaded on by unthinking parents, are ladling out mountains of homework, as in our letter “The Big Sleep.” We rejoiced when we learned that the State of Virginia had mandated recesses, and we await the day when all schools have to provide a decent lunch hour for young students, set inside a proper lunch room. We can further imagine a halcyon spring when schools have to put the sport back in sports, ensuring that every student takes part in every game, doing away with the reckless coaching that only values winning, curbing some of the injuries that crop up in perverse athletic regimes. Schools need a commitment to play. School marms and masters should take instruction from G.K. Chesterton: “The true object of all human life is play. Earth is a task garden; heaven is a playground.”

Both the great theorist of public education Horace Mann and the great child development psychologists would find reasons for a greater emphasis on real play. Mann believed that the experience of education should help teach children about democracy and community: this cannot be done without leisure and playful interchanges. Piaget found that children had to develop at their own pace, and that the pace of each child is different. Making children march fast in lockstep only guarantees that they will rush, as lemmings, over a metaphorical cliff. We have touched on the urgency of allowing children to develop naturally in “Far From the Madding Crowd: Where Silence Shouts.” They need to lighten up.

Most recently we’re hearing that an emphasis on play has a plethora of benefits for children and—we suspect –adults. “Play Then Eat: Shift May Bring Gains at School” suggests that schools that give kids a recess before lunch have discovered that their charges then eat better, have less behavior problems, and suddenly have 40% fewer health complaints. Play, it seems, is written into our DNA, and we suffer if we don’t get it.

We would suppose that the atrophy of the play organ in our brains has put the nation and our children in a terrible funk. As we have said in “Kingdom of Happiness” and “Anatomy of Melancholy,” depression has become epidemic in the developed world, and, despite its terrible costs, we don’t have a clue as to how we might deal with it. For sure the expensive outpourings of our drug factories have done nothing more than numb some of the pain. College students in a broad swathe of colleges report flashes of mental fatigue so acute that 90% of them feel unable to function during the course of the school year.

Men from La Mancha. How then do we reclaim a playful society when we have thrown the playbook away? We would suppose that we must turn to men of vivid imagination who take up improbable adventures. Such was Don Quixote, the hero of Spain’s greatest literary treasure, who tilted at windmills and imaginary enemies. Even in these rather prosaic times, there are a handful of Quixotes around who can reset the stage for all of us.

Men from La Mancha. How then do we reclaim a playful society when we have thrown the playbook away? We would suppose that we must turn to men of vivid imagination who take up improbable adventures. Such was Don Quixote, the hero of Spain’s greatest literary treasure, who tilted at windmills and imaginary enemies. Even in these rather prosaic times, there are a handful of Quixotes around who can reset the stage for all of us.

Maxwell MacLeod comes to mind. Recreating the feat of his ancestor, MacLeod rowed himself around the Hebrides a few years ago. As the Times of Londonput it, “In 1777 a Highland minister called John MacLeod made an epic 100-mile journey, rowing himself in an open boat from the north of Skye to Fuinary, on the Morven Peninsula. He did so on the instructions of the Duke of Argyll, who wanted him to oust the Jacobites in Argyll through the power of prayer.

Some 230 years later the minister's direct descendant has successfully retraced his forebear's route by rowing through the Hebridean islands in an 18ft skiff, crossing large stretches of open sea.” He’s a spanking good journalist who has done several interviews of creatively endowed leaders, a composer of poetry and doggerel, and has been known to cut quite a rug at Scottish dances. He’s at once a lover of wildlife who has warned us off the farmed salmon that comes out of Scotland these days but, as well, a passionate huntsman. We’re certain that he transformed himself into the John MacLeod of 1777 as he flitted across Scotland’s coastal waters.

Charlie Skelton, too, has taken some unlikely journies. Graduate of Oxford, actor, writer for TV shows, an occasional pornography hack, and a very fun freelancer for the Guardian, he has flown off to the Continent with fruitless hopes of uncovering the deepest, darkest secrets of the Bilderberg Society, a once a year gathering of European influentials who accomplish little but mightily feed their egos.

We like much better his current caper—as an august olive oil baron. As he remarked in the Guardian, “Back in the summer when we purchased our little corner of eucalyptus-infested paradise in an area of Portugal as far from an airport as you can get, we had no idea that what we'd actually bought was an olive farm. All we wanted was somewhere quiet to live where we could watch the collapse of civilisation in moderate safety, pick figs and eat custard tarts. Our own private Waco. We're not farmers, our forearms are hopelessly untanned, our hands are gnarled only from clicking on too many internet videos about geopolitics.” Now he’s even done his harvest, and discovered that his fling with olives has turned into a hard slog. “Oh God, I've become an olive bore. It's what comes from thinking about nothing else for a month. Angsting over maggots, flapping over quotas, weighing bucket after bucket on bathroom scales, picking olives, processing olives, dreaming about olives. Loving olives.”

But MacLeod and Skelton show us how to be players—the taking up of unlikely, other-worldly pursuits and seeing them through to the end, maggots and all. They are part of an antic tribe. Whether at sea or amidst overgrown olive vines, they remind us of Moon and company in Peter Matthiessen’s At Play in the Fields of the Lord. Caught up in extreme circumstance, they are but buffoons on life’s stage. Yet their travails partake, too, of divine comedy.

Language of Despair. A 1,000 things around us crowd out play. That’s why we have to get to sea or wind through the olive groves of Portugal. There we free ourselves of the baggage that inhibits play. Isn’t it ironic, of course, that kids of all ages get so submerged in ennervating computer games that they have no time for play? Or that we have migrated from the world of radio, where one had to use one’s imagination to picture the characters talking to us in a weekly drama, to giant, obtrusive television screens that throw sounds and images at us, making us passive, dull-witted receptors rather than interactive participants in our entertainments. It is arguable that technology on all fronts has dulled our minds and curbed our playfulness. Technology has taken control of us, because we have failed to control it.

There’s a time when all the flotsam and jetsam around us becomes too much, and it’s time to strike out from it all. Ishmael in Moby Dick muses about this sensation: “Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people's hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.”

We suspect that all our media—newspapers, cable channels, internet—not only occupy too much of our lives, but are loose enough cannon to suppress our playful instincts. That is, financial pressures and distorted interpretations of the First Amendment, have led them all to become trumpets of crisis and doom. Their cash registers ring when they can merchandise mayhem, so that our daily fare, from all sides, is about a world in meltdown and about risks and terrors we supposedly must avoid. Unfortunately their disease is catching.

Some years ago trendy thinkers peddled a brand of psycho babble called neuro- linguistic programming. It never achieved respectability in either academic or therapeutic circles. But, oddly enough, there’s something to it. In the roughest sense, it suggested that there’s a deep connection between the ways we express ourselves and our psychic wellbeing. Arguably, if our speech gets littered with alarms and fears and hopelessness, we can never be happy warriors.

There are network effects that are exactly opposite of what economists surmise. That is, as more and more people buy into the panics peddled by the media, the goods we cherish, such as happiness and play, probably diminish. Society begins to ape the dismal worldview and abortive notions pouring out of the electronic media. To wit, we must hope to get better plays on life’s stage once again.

P.S. Right up to the present day, the good, grey Times has had melancholy in its bloodstream. The paper, on the one hand, is a magnificient national resource, the like of which exists in no other nation. But, on the other, carp and dagger do stroll down its hallways, as many of its workers will tell you. If truth be told, the secret bible of the Times is the Anatomy of Melancholy. (Read the history here.)

P.P.S. It’s almost axiomatic that the media is never focused on the risk that deserves our attention. “Unintended acceleration” has been around for years, ranging back to troubles with Audis. Then the media pooh-poohed it, essentially agreeing with motor town’s defenders who attributed runaway cars to poor driving. Now we’re dealing with Toyota which is trying to sweep the problem under the rug, in this case blaming acceleration on car mats and now faulty accelerator pedals. It is rather obvious that there are not enough systematic checks and balances in car systems to stop them when things go astray. Assuredly larger defects, well beyond those that have been revealed, plague the Toyota Production System. The journalists are focused on a small subset of its problem, although some essayists are now writing about the intrinsic flaws of character in the whole of Toyota.

P.P.P.S. The Esalen Institute is where Fritz Perls and all the neuro-linguistic guys spun all their webs. Before it struck gold as a week end getaway for affluent Californians seeking a makeover, this was a simple place in Big Sur where you could get very good baked bread and enjoy the hot springs. It had always been known as either Big Sur or Slate’s Hot Springs. Then one of the Murphy sons took over and converted it into a sainted space for San Franciscans with a few bucks in their pockets who wanted to get in touch with their inner, inner souls. As we have said, all the psychological mumbo jumbo that has come out of the place is treated with a wary eye by academics. But, and it is a big ‘but,’ the whole shebang was a great deal of fun, all part of a time when Northern California seemed to be one big playground. Murphy’s best phantasy, however, was a little book called Golf in the Kingdom, which sold a skillion copies. It’s a much better deal than Esalen which lost all its charm when it went bigtime. Despite America’s bloody excursion in Vietnam and the venom that coursed through our politics, the sixties in the United States was a fun, bumptious time where people still boldly talked of the future and when we better dealt with the changes that global and domestic circumstance brought to our door.

P.P.P.P.S. All sorts of experts contend that the brain cannot properly develop without play. As well, a host of commentators strongly link creativity to play: by implication, the inventiveness of our society falters for the lack of play.

P.P.P.P.P.S. One has to be wary of games on so many fronts. Both children and adults fill their hours with computer games, but it’s hard to say that any of this is play. Addiction, yes. Play, no. Game theory simply teaches you how to gang up on someone.

P.P.P.P.P.P.S. We need playfulness to deal with daily life. But, in war, play is yet more vital. Afghanistan, for instance, pushes back the Taliban by taking up cricket. “Bottom of the ICC pile two years ago, Afghanistan came within one win of qualifying for the 2011 World Cup last April and have another chance to join cricket’s top table when the qualifying tournament for the next World Twenty20 begins in Dubai next week. Two teams will join the bigger fish in the Caribbean in April.” Amidst the carnage, Iraq topped the soccer charts in 2007. “In 2007, Iraq won the 2007 AFC Asian Cup, and became the 2007 AFC team of the year, Al-Ahram's 2007 Arab team of the year, World Soccer Magazine's 2007 World team of the year.” Having fun is a great way of dealing with a world asunder. In Boccaccio’s Decameron, 7 women and 3 men flee the city to escape the Black Death (bubonic plague), each telling a tale to while away the time as they wait things out at their villa.

P.P.P.P.P.P.P.S. In A Confession, Tolstoy recounts the horrible battles, laced with huge bouts of depression, that he fought in trying to find the meaning of life. As he turns to spiritual investigations, he finds that institutional religion and all the great thinkers are as much into false notions as truth. The religiosity of simple people speaks to him with more authenticity than anything he encounters in the theologians. More broadly, we can say that the things we ultimately find most valuable are shunted aside by the conventions, the leadership, and the institutions of our society. Today we say that government, particularly government borrowing, ‘crowds out’ private endeavors. Freud as well paints the inevitable conflict between the needs and instincts of the individual and the demands of society in Civilization and Its Discontents, a book that was published in Germany in 1930 as the world was working its way into Depression.

Home - About This Site - Contact Us

Copyright 2009 GlobalProvince.com